Focus on the By Pass Heuristic

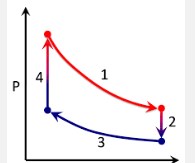

In college level physics advanced students meet a refined application of the By Pass heuristic in thermodynamics, where the effect of a transition from a state A to a state B is computing by introducing a fictitious state C. Like in this diagram:

Yet even 4 year olds have been observed applying the By Pass heuristic. But when a horse by passes an obstacle to attain a desired location --is it truly applying the By Pass Heuristic ?

Elsewhere on this site I have characterised the strategies of beginners and experts

in solving formidable problems (called Dragons and

Monsters and also

geckos in qualitative physics and mathematics

in terms of clustered bundles of problem solving ideas called heuristics

of which the earliest forms of such 'powerful ideas' are displayed by children.

One such heuristic I called Process in MIT AI Memo 338 - but on this web page its called By Pass.

This heuristic is a bundle of problem-solvings centred on the notion

that if one can't readily understand what goes on in

a transition from some state a to another state B,

one may invent 'fictitious' intervening states,

and the outcome will clarify. Statedly like so -- Process

sounds infinitely complex, but lets look at it in practice.

In MIT Artificial Intelligence

Laboratory Memo 338,

Harvey A. Cohen, The Art of Snaring Dragons.

I described incidents in the Pepsi Game played by a five year old child during

an interview conducted in 1974 by Olivier de Marcellus, a research student of Jean Piaget,

at that time a visitor in Seymour Papert's Logo Group at the MIT AI Lab.

The Pepsi Game

A child - called Rob in the memo, was shown two small squat beakers. One was almost filled with a dark, evil, sickly sweet liquid called Pepsi. The child was asked to fill the other beaker with just the same amount of Pepsi from a bottle. This the child did most diligently, making sure that the height of Pepsi in the two identical beakers was the same. On the same table was a tall, narrow, empty measuring cyliner. The child was asked, "If the Pepsi was poured from that beaker into this, where would the top of the Pepsi be?" The child pointed to a spot on the cylinder, that was at the same height as the Pepsi level in the squat beakers. The interviewer poured the Pepsi from the just filled beaker into the cylinder. When completed, the level of the Pepsi was several times higher than in the (remaining squat beaker. The child was astonished.

The interviewer asked Rob: "If you were to tell another child, what happened, what would you say?"

Rob spread his hands out about 15 cm, and pushed them together, while saying, "The sides are squishing it up".

Other children use the terms "swish" or "squish" to describe this phenomena, but this very bright 5 year old was notable in his clear use of the BY PASS Heuristic. Clearly he replaced the actual physical situation with one in which the Pepsi was poured into a cylinder with a base just like that of the squat beakers, when the height after pouring would be just the same as before. But with his hands, Rob was pushing the sides of the 'fictitious' cylinder in, till the 'real' cylinder was produced -- thus "swishing up" the Pepsi level.

Comment

Not noted in MIT AI Memo was that on the very same day as the writer witnessed the above Pepsi Game being played at a Lexington school, I asked a MIT Professor, to play "The Milko Game"The Milko Game

From the compilation A Dragon Hunter's Box

From the compilation A Dragon Hunter's BoxHarvey: "Suppose that at the bottom of a milk bottle, but inside it touching the milk, there is a pressure sensor. Suppose now that the cream in the milk rises to the top, with no change in total volume. What would happen to the pressure."

The Professor was wary. He was sure that because I was asking this question, the obvious answer, that the pressure would remain the same, must be wrong. But why? After a little discussion, wherein I agreed that the obvious answer was wrong, Professor: "If the sides were vertical then there would be no pressure change. The sides must be important." I offered no help. But then ..

Professor: "Its important that this is a milk bottle".

"Suppose one first straightened out the sides of the bottle, when its contents were milk, and first let the cream separate, and second push in the sides back to the normal bottle shape."

While running though this , the professor held his hands in front of him about 25 cm apart, with hands sloping inwards to indicate the inclined side of a milk bottle, then moved his fingers backwards making his hands vertical to indicate the straightening of the bottle. And to return the "bottle" to normal he returned his fingers to a slope.

Professor: "When the sides are straight, there is no pressure change.

Professor: "When there is cream on top, straightening and unstraightening would have little effect, since cream is light"

Professor: "But when the original milk bottle holding milk is straightened out, there will be a significant drop in pressure." Professor: "Overall, there is a drop in base pressure."

See the diagram in Heuristics and the Growth of Intelligence

Comment

The point of the above was to show the same heuristic in use by both a five-year old, and an M.I.T. Professor -- the heuristic called Process in MIT AI MEMO 338 but here called BY PASS

Now, to go on to my more recent studies and observations of problem solving in other domains.

Alexander's Experiment

My son Alexander, when aged about 11, made the following simple easily reproduced experiment. Carrying a bucket of desirable feed, he enticed a donkey to a point on star-post and wire fence about 10 metres from an open gate on the fence. Then to the donkey's chagrin, he placed the bucket just over the fence. The fence, with a height of about 1.2 m , was too high for the donkey to reach down to the bucket. But the bucket of feed was clearly visible through the wires. The donkey brayed and brayed for a long time, but made no steps to get to the feed. The experiment was repeated with our horse. The horse snorted most furiously, getting more and more angry ( from an anthropomorphic perspective), getting more and more excited, started running back and forth, wilder and wilder, until in its back and forth charges it happened to pass through the gate, and saw the buckeyet ahead, and charged at it with -- this time -- its path not blocked.The simple heuristic which the horse applied could be in words described as

If your route is blocked, run hither and thither though a less jaundiced interpretation might be

If your route is blocked, actively seek a bypass

For the moment, let's just call the Horses strategy/heuristic by the name Bypass. But is it really the same heuristic BY PASS used by the MIT Professor in his solution of Milko ?